S/2021

Columbia GSAPP, Conflict Urbanism

Collaborators: Johane Clermont, Juan Sebastián Moreno, Keneilwe Ramaphosa, Zeineb Sellami

Professor: Laura Kurgan

Political action occurs under the eye of infrastructure, below its defining conditions, and sometimes, in its absence. The noxious effects of waste often affect vulnerable and poor communities, further perpetuating existing social and spatial inequalities. We understand the infrapolitics of waste as a field of dispute that defines ideas of citizenship, belonging, and territory.

Systems for waste collection and disposal represent an important yet often overlooked component of urban landscapes. Each of the five cases explored throughout this project prove that centralized landfills encourage peripheral urbanization. These landfills are often geographically located on the outskirts of major cities. The accumulation and agglomeration of refuse represent a challenge for cities both in environmental and in social terms, since the allocation of waste management facilities affect low-income communities – their usual neighbors – in a disproportionate manner.

Meanwhile, a dispersed geography of waste co-exists alongside these “peripheral” landfills, reconfiguring urban marginality. Not only are we dealing with an exclusionary system that condemns the periphery to bearing the brunt of the noxious effects of waste, but this system breeds a marginality within, from informal settlements to informal economies.

The trash we produce is part of an intricate array of urban infrastructure that manifests itself in both formal and informal ways. From Chile, to Colombia, Haiti, South Africa, and Tunisia, this project explores the relationships between waste, the built environment, and city dwellers, through a series of maps and diagrams, to manifest the spatiality of waste flows and its impacts on informality, segregation, and dispossession.

Despite the evident urgency to tackle issues of poor waste management and to address the precarious conditions falling upon already vulnerable communities, there is an overwhelming unevenness in data availability when it comes to the ecologies of waste, particularly in our five case studies. As such, the project uses varying techniques– from satellite imagery, to archival maps, tabular data, written reports, and media platforms– to paint an accurate picture of the current conditions in each of the five case studies.

Systems for waste collection and disposal represent an important yet often overlooked component of urban landscapes. Each of the five cases explored throughout this project prove that centralized landfills encourage peripheral urbanization. These landfills are often geographically located on the outskirts of major cities. The accumulation and agglomeration of refuse represent a challenge for cities both in environmental and in social terms, since the allocation of waste management facilities affect low-income communities – their usual neighbors – in a disproportionate manner.

Meanwhile, a dispersed geography of waste co-exists alongside these “peripheral” landfills, reconfiguring urban marginality. Not only are we dealing with an exclusionary system that condemns the periphery to bearing the brunt of the noxious effects of waste, but this system breeds a marginality within, from informal settlements to informal economies.

The trash we produce is part of an intricate array of urban infrastructure that manifests itself in both formal and informal ways. From Chile, to Colombia, Haiti, South Africa, and Tunisia, this project explores the relationships between waste, the built environment, and city dwellers, through a series of maps and diagrams, to manifest the spatiality of waste flows and its impacts on informality, segregation, and dispossession.

Despite the evident urgency to tackle issues of poor waste management and to address the precarious conditions falling upon already vulnerable communities, there is an overwhelming unevenness in data availability when it comes to the ecologies of waste, particularly in our five case studies. As such, the project uses varying techniques– from satellite imagery, to archival maps, tabular data, written reports, and media platforms– to paint an accurate picture of the current conditions in each of the five case studies.

Centralized landfills encourage peripheral urbanization

We begin our exploration with a premise that underlines the uneven character of urbanization and, in a parallel way, of the burden of waste. Landfills represent a potent contradiction in infrastructure, and conflicting urban forces gravitate around them. While landfills function in the realm of formality, as nodes in vast networks of waste collection and disposal, they are simultaneously powerful catalysts for informal development. Two case studies will help us understand the effect of centralized landfills in peripheral urbanization.

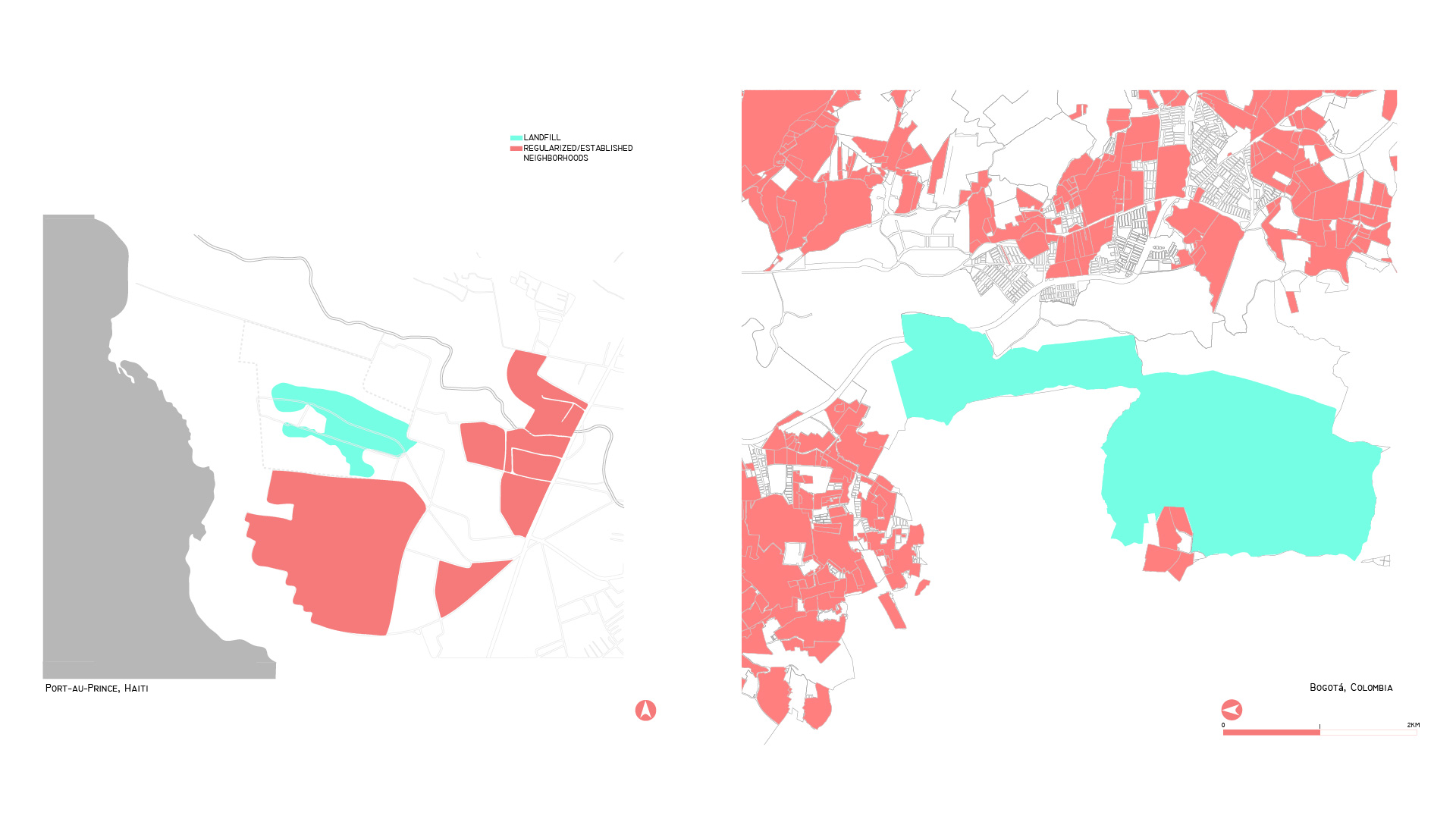

Doña Juana is the only operating landfill in Bogotá, Colombia. It receives 6,300 tonnes of waste everyday, which are then buried in an extension of 592 hectares in the southeastern border of the city. It was opened in November, 1988, after a series of overlapping crises resulted in the closure of the previous two facilities where waste was buried. Since then, Doña Juana’s influence - in contamination and urbanization - has only grown.

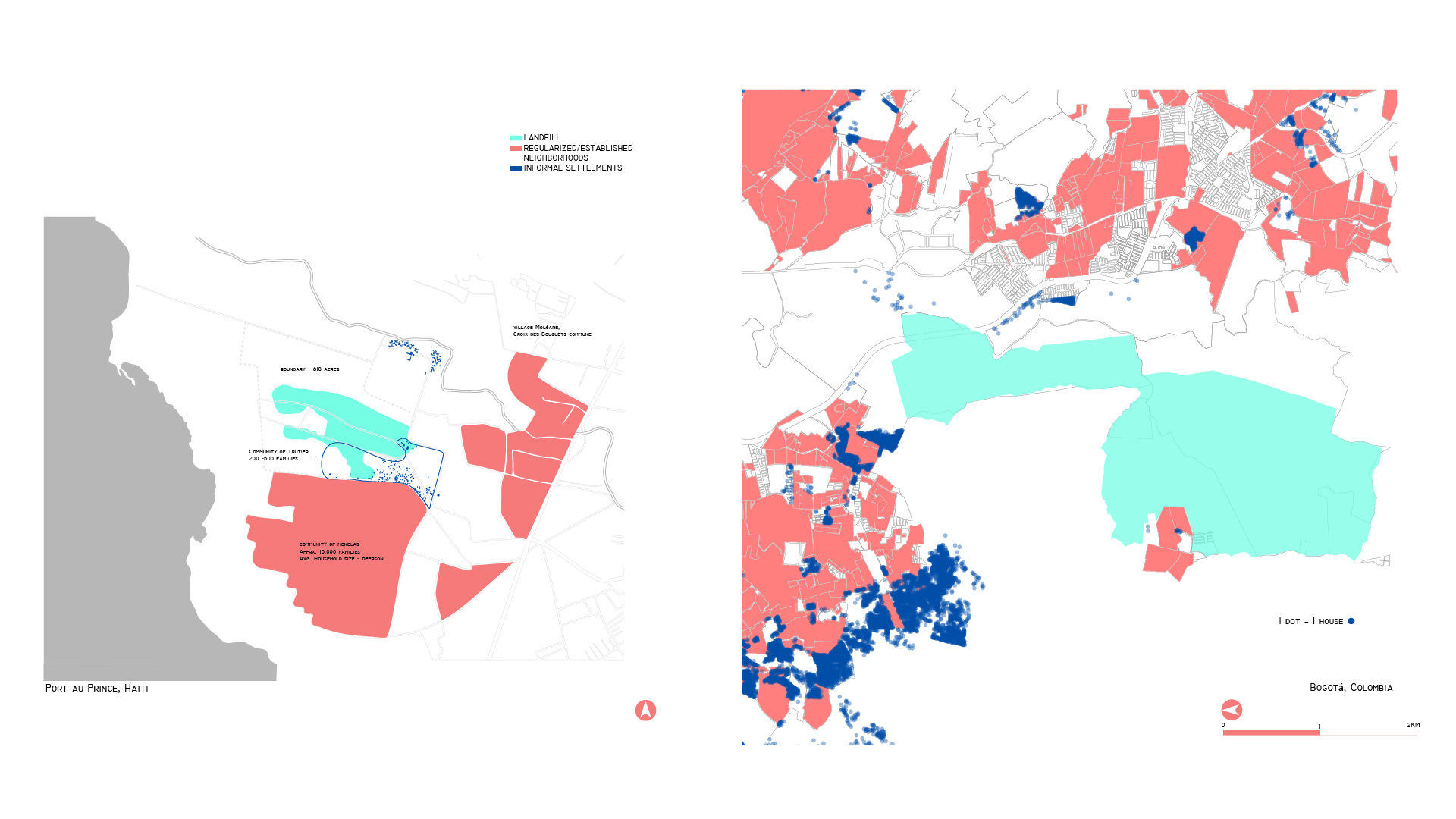

Similarly, Truitier is the only landfill in Port-au-Prince (PAP), created in 1980 on 618 acres of land in the municipality of Cité Soleil, a densely populated and extremely poor commune. It serves Port-au-Prince and its seven municipalities, which produce between 1,400 and 1,600 metric tonnes of waste each day. A dozen private operators collect 20% of rubbish, while the informal sector handles 10%, and the Metropolitan Service for Collecting Solid Waste (SMCRS), an autonomous entity under the Ministry of Public Works (MPW), collect 30%.

Around both landfills, the drive for informal urbanization is not antagonistic to public intervention. Instead, they often go hand-in-hand and they acquire a salient nature when informal settlements are formalized. As Anaya Roy (2005:150) explains, “the legalization of informal property systems is not simply a bureaucratic or technical problem but rather a complex political struggle.”

The main formalization strategy in Bogotá has been a program to “regularize” neighborhoods. Regularization, for city administrations of different political colors, has represented a similar process of allocating public resources to previously underserved informal settlements, extending service networks, building asphalt roads and concrete sidewalks, and starting social outreach programs. Between 1952 and 2020, Bogotá transformed 1,787 informal settlements into formal neighborhoods. The highest number of regularizations occurred between 1986 and 2000, when 1,057 settlements of informal origins were added to the city’s inventory of formal settlements.

However, recent trends in peri-urban development around Doña Juana has shown that neighborhood regularizations have had little effect curtailing the growth of new informal settlements. New informal dwellings are still being produced as a result of overlapping forces: a relative scarcity of land readily available for new development; a connection to the local informal economy; and infrastructure provision centered around the landfill.

Doña Juana is the only operating landfill in Bogotá, Colombia. It receives 6,300 tonnes of waste everyday, which are then buried in an extension of 592 hectares in the southeastern border of the city. It was opened in November, 1988, after a series of overlapping crises resulted in the closure of the previous two facilities where waste was buried. Since then, Doña Juana’s influence - in contamination and urbanization - has only grown.

Similarly, Truitier is the only landfill in Port-au-Prince (PAP), created in 1980 on 618 acres of land in the municipality of Cité Soleil, a densely populated and extremely poor commune. It serves Port-au-Prince and its seven municipalities, which produce between 1,400 and 1,600 metric tonnes of waste each day. A dozen private operators collect 20% of rubbish, while the informal sector handles 10%, and the Metropolitan Service for Collecting Solid Waste (SMCRS), an autonomous entity under the Ministry of Public Works (MPW), collect 30%.

Around both landfills, the drive for informal urbanization is not antagonistic to public intervention. Instead, they often go hand-in-hand and they acquire a salient nature when informal settlements are formalized. As Anaya Roy (2005:150) explains, “the legalization of informal property systems is not simply a bureaucratic or technical problem but rather a complex political struggle.”

The main formalization strategy in Bogotá has been a program to “regularize” neighborhoods. Regularization, for city administrations of different political colors, has represented a similar process of allocating public resources to previously underserved informal settlements, extending service networks, building asphalt roads and concrete sidewalks, and starting social outreach programs. Between 1952 and 2020, Bogotá transformed 1,787 informal settlements into formal neighborhoods. The highest number of regularizations occurred between 1986 and 2000, when 1,057 settlements of informal origins were added to the city’s inventory of formal settlements.

However, recent trends in peri-urban development around Doña Juana has shown that neighborhood regularizations have had little effect curtailing the growth of new informal settlements. New informal dwellings are still being produced as a result of overlapping forces: a relative scarcity of land readily available for new development; a connection to the local informal economy; and infrastructure provision centered around the landfill.

In 2010, within thirty-four seconds, a 7.0 magnitude earthquake crumbled four major cities including Port-au-Prince. The earthquake exacerbated all issues in PAP, including waste management. The earthquake produced millions more tons of waste. As part of the recovery efforts, Direction Nationale de l’Eau Potable et de l’Assainissement (DINEPA), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) began efforts to incorporate renewable energy and aerobic biodigestion technology (biogas) as part of the sanitation solution for Haiti. Truitier was one of six selected sites studied and chosen to become an anaerobic digestion (AD) process that breaks down biodegradable material–facility.

Then, 78 people were officially employed by SMRCS and over 100 informal sorters earned a living sorting and reselling materials. These sorters were part of the informal community residing on site, which operated 24 hours a day. Today, that informal community is now 200-500 families living on the edge occupying fragile shelters composed of cloth and wood and still foraging through miles of toxic trash for food and materials to resell to earn a living. The proposed AD facility was never developed. The site lacks working equipment, drainage systems, a waste separation location, and most significantly capital, it would cost an estimated $370 million to increase solid waste collection from 20 to 90 percent by 2022.

Doña Juana’s presence has incentivized new informal developments by being an infrastructural anchor to the types of networks that are rarely accessible to new peri-urban settlements. The landfill is a form of locational capital crystallized as infrastructure, representing both the promise of formalization and the physical and symbolic extension of the city’s frontier. In an analogous movement, Truitier is a node of formal and informal economic activity. Despite the environmental degradation and health risks, or hell on earth, as described by current sorters, working in the landfill is an opportunity to make a living.

Placing and operating landfills represents the allocation of multiple burdens on the environmental and social infrastructure of a city. The first type of burden is a form of contamination that is both vertical and horizontal. It spreads in simultaneous manner through the air, the land, the soil, the undercurrents and the human settlements in between. Landfills are not only “garbage graveyards,” but festering wounds on the urban fabric.

They are not static, either. As cities expand, so do landfills. For this reason, the environmental cost of urban growth is unevenly placed on the landfills’ neighbors. In Latin American and Caribbean cities, centralized waste management has exacerbated patterns of urban informality, and created places where poverty meets toxicity and dispossession acquires multiple meanings.

Then, 78 people were officially employed by SMRCS and over 100 informal sorters earned a living sorting and reselling materials. These sorters were part of the informal community residing on site, which operated 24 hours a day. Today, that informal community is now 200-500 families living on the edge occupying fragile shelters composed of cloth and wood and still foraging through miles of toxic trash for food and materials to resell to earn a living. The proposed AD facility was never developed. The site lacks working equipment, drainage systems, a waste separation location, and most significantly capital, it would cost an estimated $370 million to increase solid waste collection from 20 to 90 percent by 2022.

Doña Juana’s presence has incentivized new informal developments by being an infrastructural anchor to the types of networks that are rarely accessible to new peri-urban settlements. The landfill is a form of locational capital crystallized as infrastructure, representing both the promise of formalization and the physical and symbolic extension of the city’s frontier. In an analogous movement, Truitier is a node of formal and informal economic activity. Despite the environmental degradation and health risks, or hell on earth, as described by current sorters, working in the landfill is an opportunity to make a living.

Placing and operating landfills represents the allocation of multiple burdens on the environmental and social infrastructure of a city. The first type of burden is a form of contamination that is both vertical and horizontal. It spreads in simultaneous manner through the air, the land, the soil, the undercurrents and the human settlements in between. Landfills are not only “garbage graveyards,” but festering wounds on the urban fabric.

They are not static, either. As cities expand, so do landfills. For this reason, the environmental cost of urban growth is unevenly placed on the landfills’ neighbors. In Latin American and Caribbean cities, centralized waste management has exacerbated patterns of urban informality, and created places where poverty meets toxicity and dispossession acquires multiple meanings.

Dispersed geographies of waste reconfigure urban marginality

The previous section shows how communities living around landfills engage in forms of resistance that lead them to create forms of daily life which gravitate around the presence of waste without letting it define them.

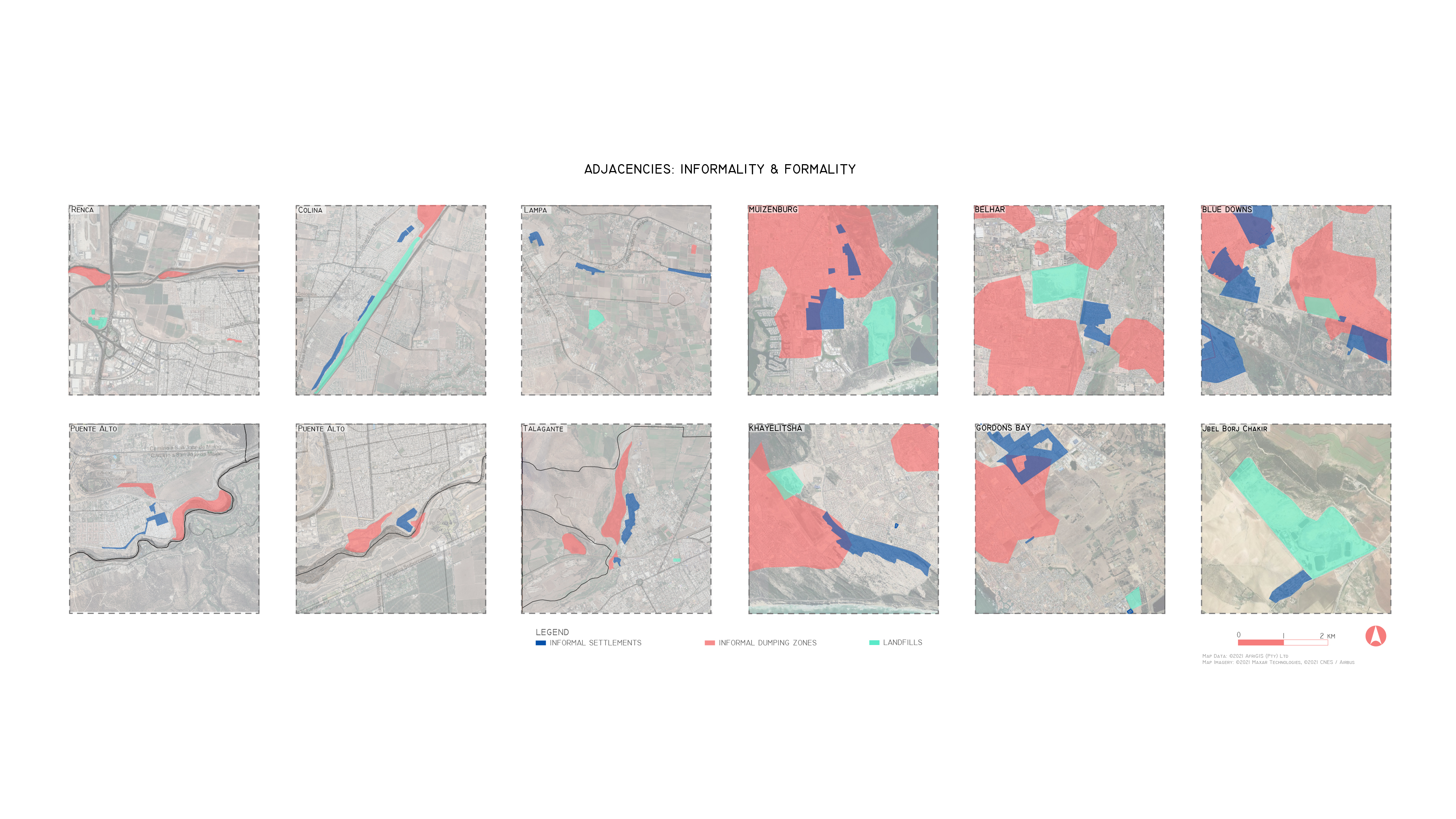

The toxicity of the landfills themselves – i.e., the environmental and health damage it causes to those living in their proximity – and the dangerous conditions thus imposed on networks of informal waste pickers, are evidence of collapses in established systems, which are failing to properly dispose of solid waste and thus transferring the burden of waste management and recycling onto the city’s most vulnerable communities (MEO, 2019). In the face of the deficiencies of central and local governments, informal waste management systems emerge within the heart of cities.

In the city of Santiago, waste gets dispersed from within the city to its periphery, ending up as a new geography of garbage that hovers over vulnerable communities. There are 79 “mega-wastelands” (more than 1 acre), but there are over 600 “micro-wastelands” (less than 1 acre) distributed in the lower income areas of the city (Bravo, 2019). Of these, 43 informal landfills imply a health risk to those who inhabit around them, compromising the many informal settlements or “camps” in their proximity (SEREMI, 2012). The Metropolitan region, where the capital and its peripheries are located, generates 44.9% of Chile’s waste, equivalent to 360.451 tons of waste, for a density of 7.11 million inhabitants. According to the Ministry of Environment, 96.3% of this waste gets properly collected and placed on formal landfills (SEREMI 2017).

The toxicity of the landfills themselves – i.e., the environmental and health damage it causes to those living in their proximity – and the dangerous conditions thus imposed on networks of informal waste pickers, are evidence of collapses in established systems, which are failing to properly dispose of solid waste and thus transferring the burden of waste management and recycling onto the city’s most vulnerable communities (MEO, 2019). In the face of the deficiencies of central and local governments, informal waste management systems emerge within the heart of cities.

In the city of Santiago, waste gets dispersed from within the city to its periphery, ending up as a new geography of garbage that hovers over vulnerable communities. There are 79 “mega-wastelands” (more than 1 acre), but there are over 600 “micro-wastelands” (less than 1 acre) distributed in the lower income areas of the city (Bravo, 2019). Of these, 43 informal landfills imply a health risk to those who inhabit around them, compromising the many informal settlements or “camps” in their proximity (SEREMI, 2012). The Metropolitan region, where the capital and its peripheries are located, generates 44.9% of Chile’s waste, equivalent to 360.451 tons of waste, for a density of 7.11 million inhabitants. According to the Ministry of Environment, 96.3% of this waste gets properly collected and placed on formal landfills (SEREMI 2017).

In Cape Town, the ever present remnants of South Africa’s Apartheid spatial planning perpetuate inequalities across demographics, in addition to disproportionate service provision in different socioeconomic groups and geographies. Different tiers of waste management, informal dumping tolerance, and formal landfill adjacency correlate to socioeconomic status and property values. Those closest to landfills with the least efficient municipal waste management are those living in poverty in informal settlements on the outskirts of the city. High-income households generate the most waste and receive the best waste management service provisions by the government. They are located furthest from landfills and suffer the least from issues around informal waste disposal. Most informal settlements don’t receive weekly door to door waste services therefore 9.2% of South African households will resort to using informal dumping sites. (APWC, 2020)

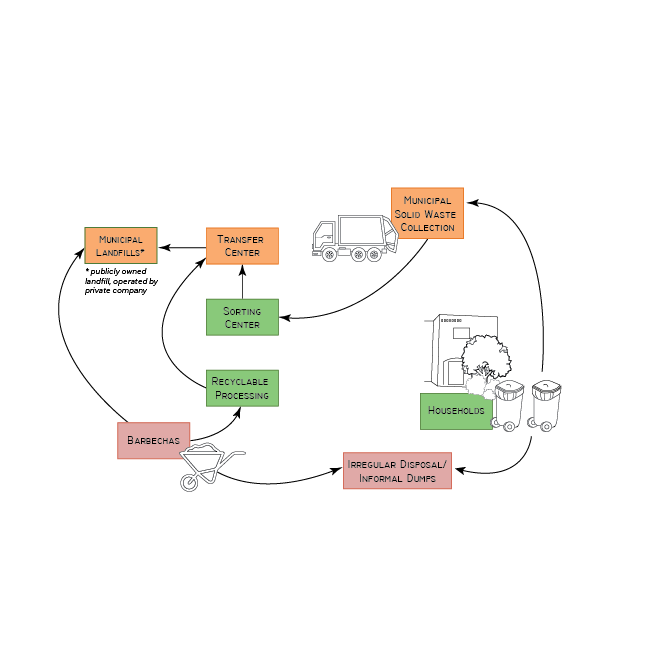

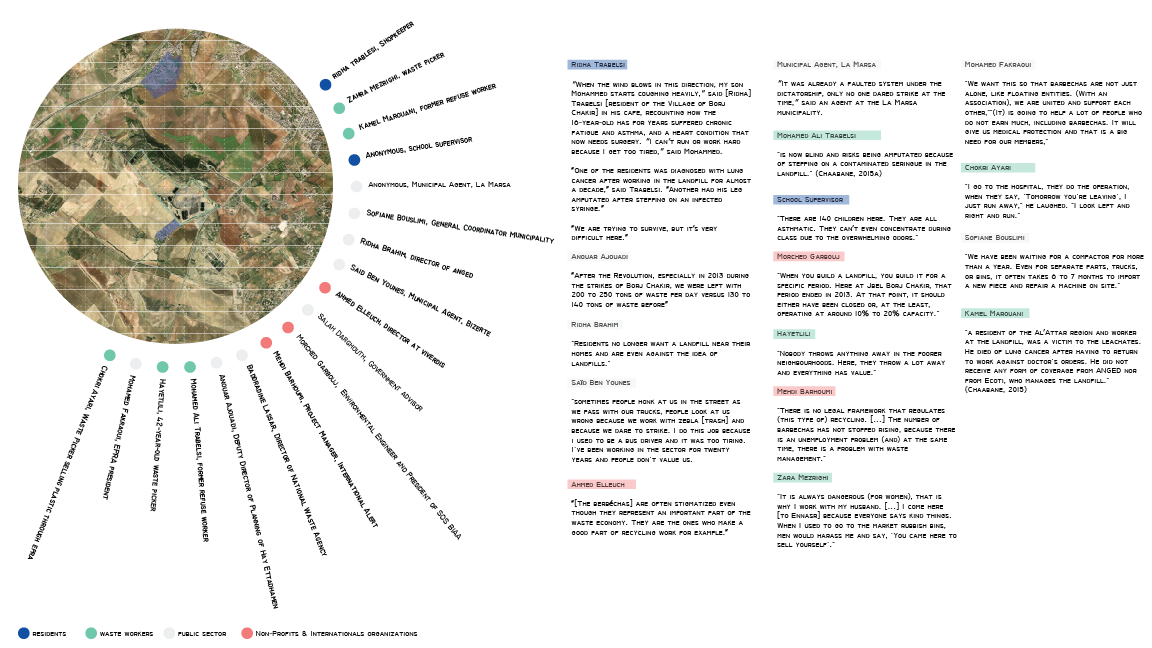

Finally, in Tunis, Jbel Borj Chakir, located in the suburbs of the Tunisian capital, is one of the country’s largest landfills, employing nearly 80 workers (Bocchi, 2017) and spanning nearly 120 hectares of previously agricultural land. This landfill, along with the ten other active landfills in the country, often located in urban peripheries (and on the border of administrative lines), cater to about one third of the country’s urban population (World Bank Report, 2014). The other two thirds of the population rely on about 400 uncontrolled and undocumented dumping sites, along with an intricate network of an estimated 15,000 informal waste pickers called barbéchas (World Bank Report, 2014; Fouroudi, 2019). Since the 2011 Revolution, clashes between national and municipal authorities, private actors, villagers living in proximity to landfills, and the barbéchas have escalated (Mahjoub et. al, 2020) leading to a number of governmental and non-profit responses addressing the infrastructure of waste.

Finally, in Tunis, Jbel Borj Chakir, located in the suburbs of the Tunisian capital, is one of the country’s largest landfills, employing nearly 80 workers (Bocchi, 2017) and spanning nearly 120 hectares of previously agricultural land. This landfill, along with the ten other active landfills in the country, often located in urban peripheries (and on the border of administrative lines), cater to about one third of the country’s urban population (World Bank Report, 2014). The other two thirds of the population rely on about 400 uncontrolled and undocumented dumping sites, along with an intricate network of an estimated 15,000 informal waste pickers called barbéchas (World Bank Report, 2014; Fouroudi, 2019). Since the 2011 Revolution, clashes between national and municipal authorities, private actors, villagers living in proximity to landfills, and the barbéchas have escalated (Mahjoub et. al, 2020) leading to a number of governmental and non-profit responses addressing the infrastructure of waste.

In South Africa, local municipal governments are responsible for solid waste management and collection infrastructure. “239 municipalities collect waste in 8.4 million households using direct labour, appointed contractors or community co-operatives.” (APWC, 2020) The bulk of all unseparated solid waste is collected by municipalities and transported to formal landfills. In unregulated areas, such as informal settlements, there’s little to no formal waste management services. Communities will resort to burning, burying or dumping their waste anywhere within the surrounds of their informal settlements (i.e. empty fields/parks, curbsides, etc). Informal reclaimers extract recyclables from private/public bins, and both formal landfills and informal dumping zones for self utilisation or to sell to recyclable collection companies and brokers who in turn buy and sell to recyclable processing companies. In the informal settlements, informal reclaimers often provide the only waste management services.

Santiago is an example on how poverty distribution is linked directly to waste mismanagement, and it’s informal disposal. The Ministry of Environment has extended plans for healthy management of waste, but these policies get applied only on high-income areas of the city. As recycling points multiply on these sectors, the rest of the city has multiplying micro wastelands.

In Cape Town, waste management tiers are hierarchical regarding waste management service provision to formal and informal households but formal and informal waste management service providers have a symbiotic relationship and sustain each other.

Santiago is an example on how poverty distribution is linked directly to waste mismanagement, and it’s informal disposal. The Ministry of Environment has extended plans for healthy management of waste, but these policies get applied only on high-income areas of the city. As recycling points multiply on these sectors, the rest of the city has multiplying micro wastelands.

In Cape Town, waste management tiers are hierarchical regarding waste management service provision to formal and informal households but formal and informal waste management service providers have a symbiotic relationship and sustain each other.

Waste management in Tunisia is a complex affair between a variety of stakeholders from national to local government bodies, contracted private companies, local associations and advocacy groups, and the waste workers themselves. At the highest level, a central department within the Ministry of the Interior oversees the country’s solid waste management, developing policies, strategies, and programs. At the local level, municipalities are responsible for the day-to-day collection of waste. (Mahjoub et. al., 2020) Each municipality hires its own waste workers who collect waste (either door-to-door or from neighborhood refuse bins) and transport it to treatment facilities or directly to the landfill (Aydi, 2013). Though the collection and transport is undertaken directly by the municipalities, the landfills (and treatment centers) are operated by private companies. Finally, there are two types of barbéchas (informal waste pickers): those that work in certain neighborhoods, collecting recyclables to take to treatment locations, and those that work in the landfills themselves, collecting and triaging different forms of waste (Chaabane, 2015a).

Municipalities face barriers such as insufficient budgets, outdated equipment, and a lack of qualified personnel (Blaise, 2014). In addition to these difficulties, corruption among higher governing bodies and the private landfill operators have led to workers strikes (Bocchi, 2017). Meanwhile, central government continues to plan for an expansion of landfills, often against the will of citizens and local residents. The following country-wide map* shows plans for new landfills despite existing deficiencies and lack of stakeholder involvement.

Whether in Tunisia, Chile or South Africa, municipal shortcomings with regards to these critical pieces of infrastructure, have led to severe mismanagement of landfills and waste collection, leaving citizens with no other choice but to take matters into their own hands, spurring informal development.

Municipalities face barriers such as insufficient budgets, outdated equipment, and a lack of qualified personnel (Blaise, 2014). In addition to these difficulties, corruption among higher governing bodies and the private landfill operators have led to workers strikes (Bocchi, 2017). Meanwhile, central government continues to plan for an expansion of landfills, often against the will of citizens and local residents. The following country-wide map* shows plans for new landfills despite existing deficiencies and lack of stakeholder involvement.

Whether in Tunisia, Chile or South Africa, municipal shortcomings with regards to these critical pieces of infrastructure, have led to severe mismanagement of landfills and waste collection, leaving citizens with no other choice but to take matters into their own hands, spurring informal development.

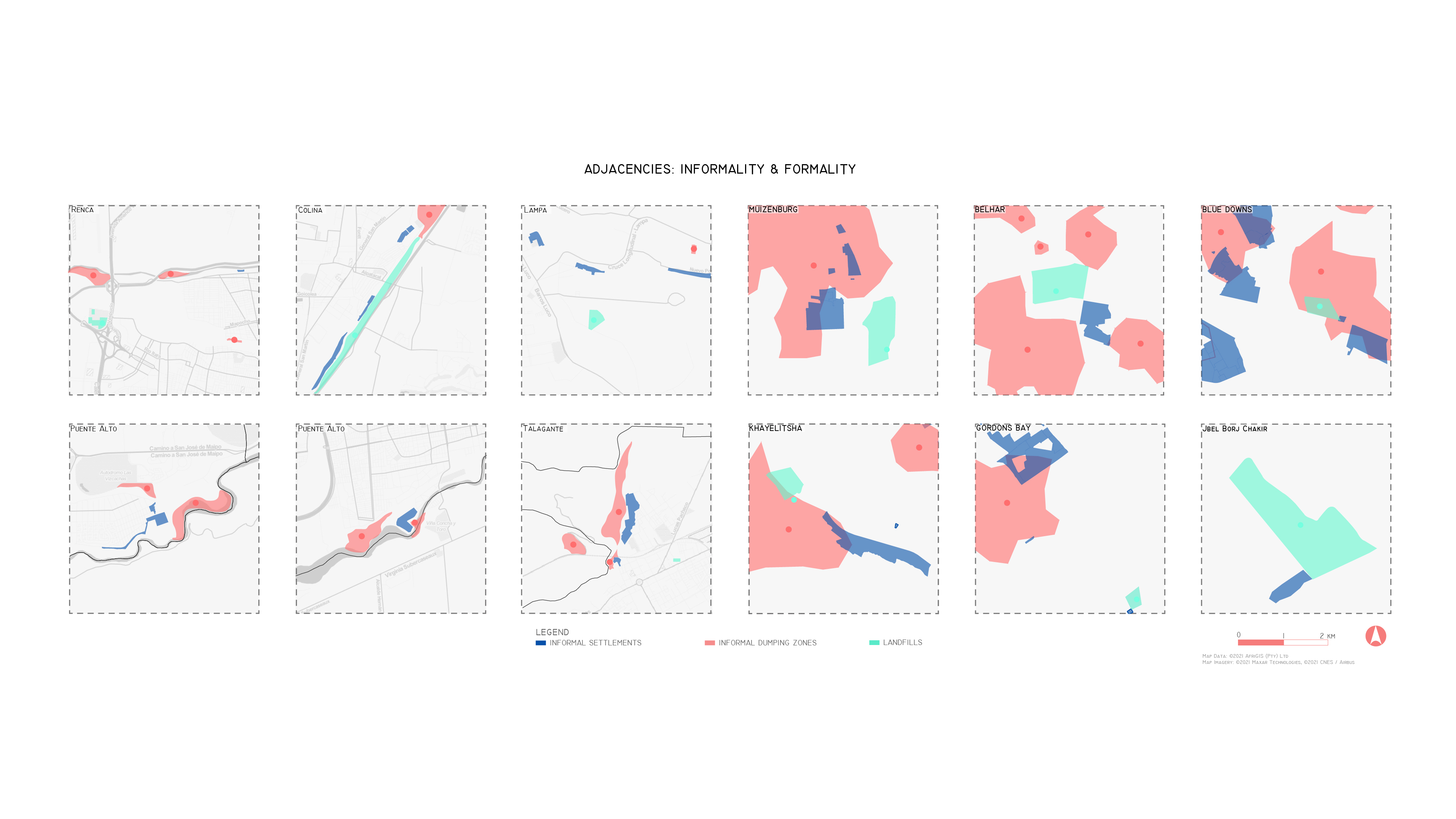

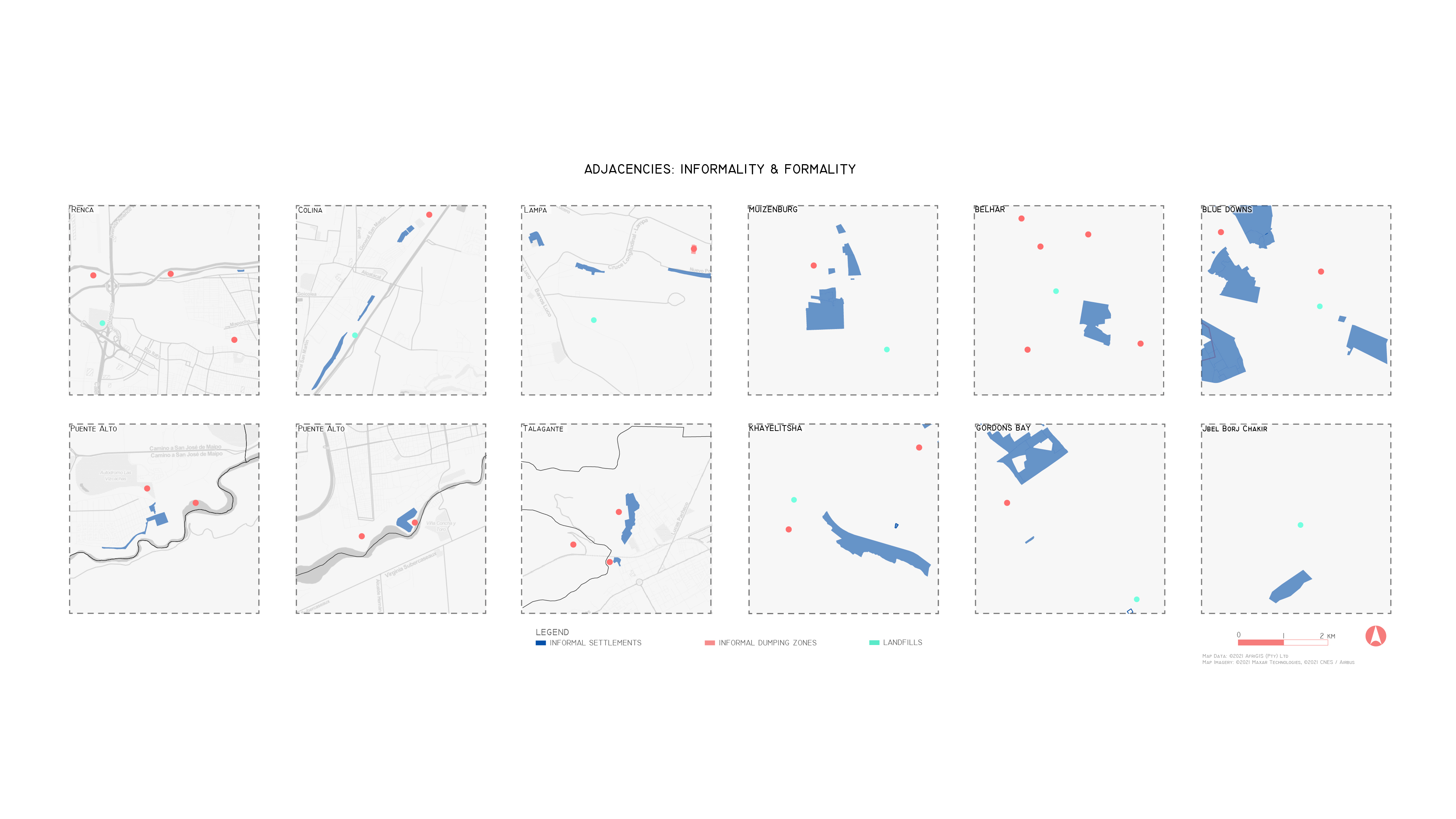

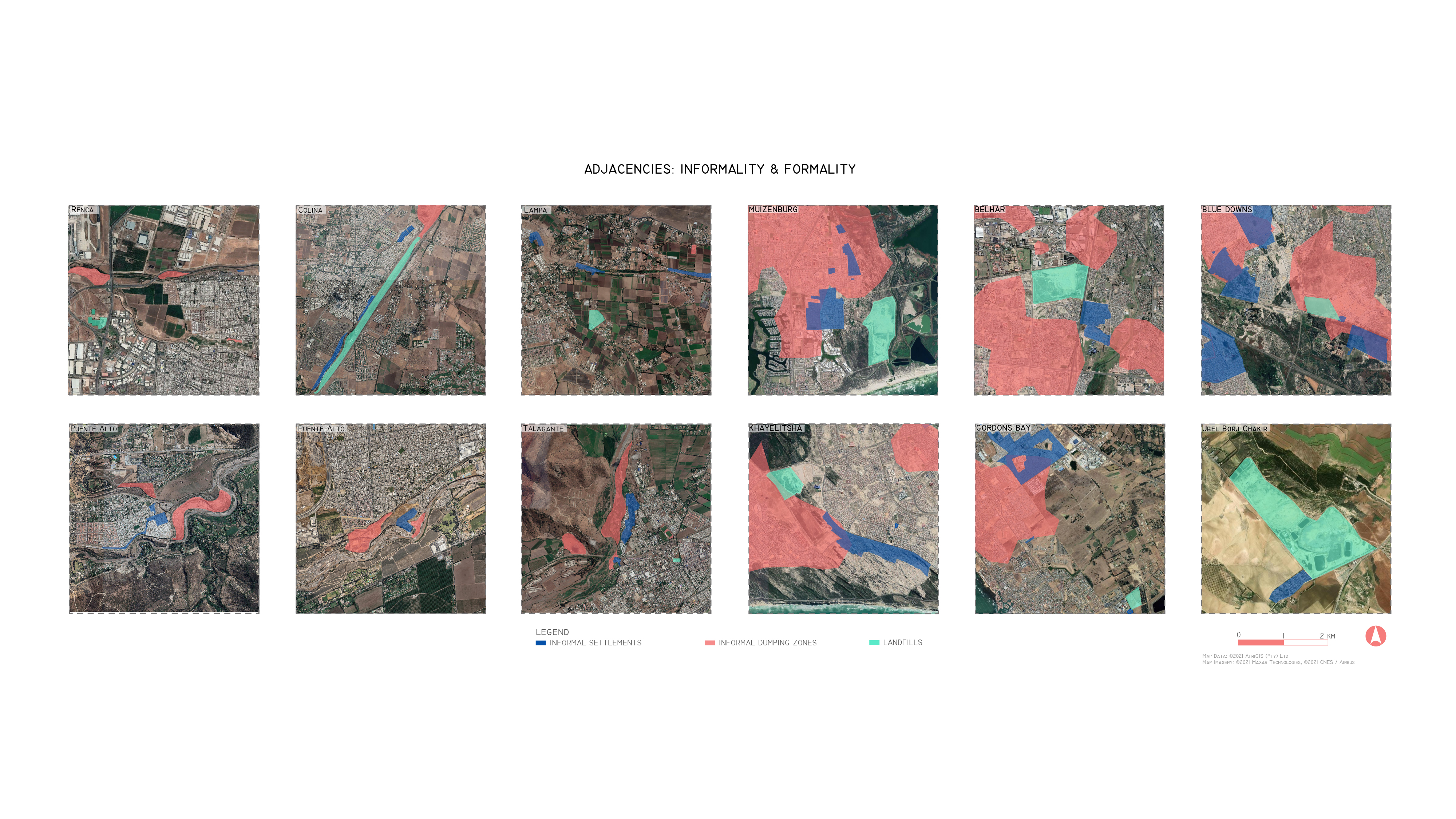

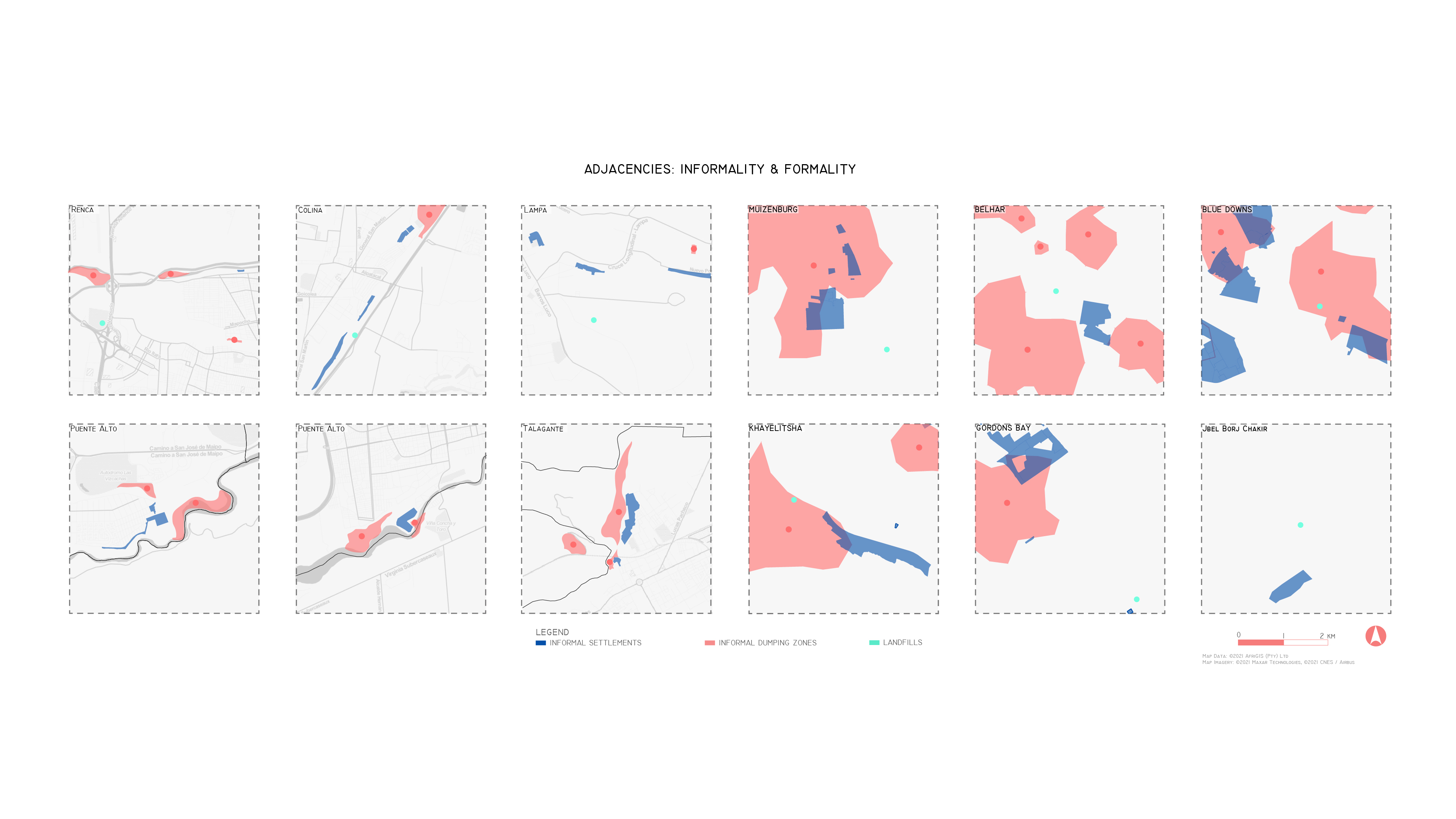

In the case of Cape Town and Santiago, informality is dispersed. The maps depict informal settlements and informal landfills, showing in both cases, higher concentration of sites on low-income neighborhoods. The circled spots are cases where informality of waste and living are superimposed, and sometimes, in close proximity to formal landfills. In the case of Santiago, informality is located mostly on borders: near the Mapocho river, on the city’s periphery or in limits between municipalities, where control is scarce.

Inequitable service delivery across demographics in South Africa is anchored in the historical legacies of colonialism and Apartheid. During the Apartheid era, under the Group Areas Act “non-white” communities were relocated to the city outskirts and the high influx of displaced people caused the rapid growth of informal settlements.

Inequitable service delivery across demographics in South Africa is anchored in the historical legacies of colonialism and Apartheid. During the Apartheid era, under the Group Areas Act “non-white” communities were relocated to the city outskirts and the high influx of displaced people caused the rapid growth of informal settlements.

Waste management service delivery provisions vary significantly between provinces, municipalities and often between neighbourhoods adjacent to each other. With little to no waste service delivery in informal settlements, occupants resort to informal waste dumping which results in unregulated, far spread informal dumping zones intersecting across many informal settlements.

The City of Cape Town spends approximately 10% of its cleansing budget, for the removal/rehabilitation of informal dumping zones. (APWC, 2020) Socio-economic inequality in Chile is visible in the way waste is handled. Most of the government’s initiatives depend on each municipality and its budget to recollect and properly dispose of waste, and given that the majority of micro or informal wastelands are located in low-income municipalities, waste is disposed of by individuals outside the governmental system. These disposal sites are located in borders between municipalities, as they are zones with less regulation.

The City of Cape Town spends approximately 10% of its cleansing budget, for the removal/rehabilitation of informal dumping zones. (APWC, 2020) Socio-economic inequality in Chile is visible in the way waste is handled. Most of the government’s initiatives depend on each municipality and its budget to recollect and properly dispose of waste, and given that the majority of micro or informal wastelands are located in low-income municipalities, waste is disposed of by individuals outside the governmental system. These disposal sites are located in borders between municipalities, as they are zones with less regulation.

Informal economies

The existence of these informal landfills and dumping sites is inherently linked to a network of informal waste pickers. In Cape Town, informal waste economies have formed around waste pickers and both formal and informal waste reclaim/recycling centres. Up to 90,000 people make their livelihood through the informal waste sector by reclaiming and recycling mainline recyclables, either on the streets or on landfill sites (Godfrey, 2016).

Meanwhile, in Tunisia, an estimated 15,000 barbéchas collect nearly two-thirds of the country’s recyclable waste (Foroudi, 2019). “Many waste pickers live in poverty, selling the waste they find to middlemen recyclers who then sell it on for a marked-up price to the national waste collection system or, more often, a private recycling factory.” “And like thousands of other Tunisians who work in the informal sector, barbechas lack an official status and lead a precarious life, carrying out their jobs without workers’ rights or health insurance, say human rights activists.”

Meanwhile, in Tunisia, an estimated 15,000 barbéchas collect nearly two-thirds of the country’s recyclable waste (Foroudi, 2019). “Many waste pickers live in poverty, selling the waste they find to middlemen recyclers who then sell it on for a marked-up price to the national waste collection system or, more often, a private recycling factory.” “And like thousands of other Tunisians who work in the informal sector, barbechas lack an official status and lead a precarious life, carrying out their jobs without workers’ rights or health insurance, say human rights activists.”

Both in Tunis and Cape Town, waste pickers enhance services provided by the government in areas that receive waste management services, providing higher recycling rates and in low income areas, often they provide the only form of solid waste collection.

The geography of waste in Bogotá extends well beyond Doña Juana, and includes more than the private trucks that collect garbage. A network of multiple dumping sites, mapped here, is mostly navigated by informal waste pickers.

Using spatial analysis on these dumping sites, we determined hotspots of waste outside the landfill. In order to tackle this issue, the city developed a formal system to integrate waste pickers into collection circuits, which consists of a series of warehouses where waste pickers go to classify, weigh, and sell the material they gather. The system’s coverage is minimal, and there are no technical solutions in place to improve or dignify the waste pickers’ work.

The geography of waste in Bogotá extends well beyond Doña Juana, and includes more than the private trucks that collect garbage. A network of multiple dumping sites, mapped here, is mostly navigated by informal waste pickers.

Using spatial analysis on these dumping sites, we determined hotspots of waste outside the landfill. In order to tackle this issue, the city developed a formal system to integrate waste pickers into collection circuits, which consists of a series of warehouses where waste pickers go to classify, weigh, and sell the material they gather. The system’s coverage is minimal, and there are no technical solutions in place to improve or dignify the waste pickers’ work.

Waste obfuscates the boundaries between formality and informality

Ananya Roy (2005) defines urban informality as a mode of governance, as the expression of sovereign power on urban landscapes that purposefully relegates swathes of the city while letting others thrive. Her definition –“informality is not a separate sector but rather a series of transactions that connect different economies and spaces to one another”– is a lighthouse for any theoretical approach to the tangible consequences of planning processes in the Global South.

Our five case studies have uncovered similar patterns of uneven urban development, illustrating the disproportionate spatial effects of waste. This is a story about infrastructure, but it is also a story of neoliberal assault on cities, as trash collection and disposal became privatized. It is also a story about resistance, environmental injustice, and emplacement in the midst of abject toxicity. Visualizing disparities in urban landscapes through the combined lens of (formal and informal) waste infrastructure and toxic environments is a way to confront the mode of urbanization imposed on cities. Contesting its political economy and its imperative to bury trash near the urban poor is, then, a political posture that refuses to declare territories and communities as disposable. Are landfills truly the only viable option for cities to dispose of their trash? Are there ways to work with and within the informal waste picking economy rather than penalizing/marginalizing it?